Making Ourselves Accountable

A systematic approach to tracking progress toward real impact at scale.

We think that funders like us should be accountable for impact, just like investors are accountable for profit. Without that we - philanthropy and aid - will only accomplish a fraction of what we might have. This is an effort to get out ahead and put our money where our mouth is.

The mission of the Mulago Foundation is to meet the basic needs of the very poor. The way we do that is to find and fund organizations with 1) high-impact, scalable solutions, and 2) the commitment and capacity to drive those solutions toward their full potential. We do not fund projects - we fund organizations that are developing, proving and moving important solutions to scale. Our funding is unrestricted and we continue to fund organizations as long as we believe that they are still on the path to impact at scale.

We think that funders should make themselves accountable for impact. If funders were accountable for impact, they’d fund better, doers would do better, and money would flow efficiently to those best able to create change. The social sector would start to function like a market for impact, which would itself cure a host of ills. All this philanthropy, all this aid, will never make more than a marginal difference if funders remain unaccountable for impact.

Our portfolio is composed of organizations that we believe are likely to achieve impact at scale. We typically invest in early-stage organizations. We accompany them as they develop the solution, replicate it themselves, achieve rigorous evidence of impact, and scale it up. We say our portfolio is composed of organizations that are taking high-impact solutions to scale. It’s on us to demonstrate the degree to which it is happening. We want to be accountable. This is how we’re doing it.

First, some definitions. “Impact,” “scale,” and even “solution” are used in many different ways throughout the social sector. These three terms are central to everything we do, and we are very specific about what they mean.

Impact

Impact is an observable, quantifiable change in terms of a specific outcome. The outcome that matters most is the one that is central to the organization or program’s mission. We work with organizations to define their missions concisely through the formulation of an “8 word mission statement” that includes a verb, a target population or entity, and the most important outcome. Some examples: “Save children’s lives in Sub-Saharan Africa,” “get Indian smallholder farmers out of poverty,” “create good jobs in urban slums,” and “save coral reefs in the South Pacific.” Those outcomes must be captured by well-selected metrics, and an organization’s impact is the degree to which it achieves its stated mission in terms of those metrics: An organization’s impact = an outcome + a change. Put another way, an organization’s impact is the difference between what it accomplished and what would have happened without it. It’s worth noting that we look for impact that is both proven and meaningful: a change can be statistically significant but not big enough to be interesting.

Scale

Scale isn’t just another word for growth, and it isn't the achievement of some number - even an impressive-sounding number like a million. For us, scale is the distant dream of achieving the full potential of a solution. Scaling means busting out of a linear trajectory into a non-linear, ever-steepening curve of impact over time. The journey to scale doesn’t end until a solution has achieved its potential for impact: It’s been implemented everywhere that it is a) needed, and b) would work effectively. Sure, scale can be captured by numbers, but even a million pales in relation to a need on the order of a billion. The problems we’re all trying to solve are enormous, and the attainment of a big number should spur us toward the next order of magnitude. If scaling means that a solution achieves and sustains a continually steeper rate of replication, then it is almost always the case that it requires the recruitment and facilitation of other organizations to replicate the solution as well. That is not easy, and few do it well - at least not yet.

Solution

A solution is an idea that becomes something doable and systematic in a way that can go big - big enough to make a big dent in a big problem. We’re talking about scalable solutions. A scalable solution has five distinct elements:

- A Big Idea that drives and organizes it.

- A Mission that focuses the idea on a specific outcome.

- A Model that lays out a systematic and replicable way to apply that theory.

- A Strategy that identifies who is going to replicate the model at problem-solving scale and who is going to pay for all that replication. We call them the doer-at-scale and the payer-at-scale.

With those definitions as the foundation, we’ll describe how we think about the journey to scale, and how we use the resulting framework to drive our due diligence and the decision to get in, how that same framework guides our portfolio management and the ongoing decisions to stay in or get out. The result is accountability; a way to judge whether, at any point in time, the organizations that we fund are making promising progress on the journey to scale.

It’s important to note here that solutions funding is different from simply funding organizations. No solution can get to scale without an organization (and eventually a set of organizations) obsessed with getting it there, and as a funder, your job is to find them and supply the money that lets them drive the solutions forward. However, our obligation is to the solution, and our interests as funder and their interests as doer can only align insofar as we are both pushing the same solution forward.

When We Get In

Initial Diligence.

We fund when we are convinced that an organization:

- Is focused on a basic need of the poor.

- Has a scalable solution

- Has a commitment to scale and a team that can deliver.

Basic needs.

These include typical things like basic education, healthcare, and livelihoods, but we’ve also become involved in other issues that disproportionately bedevil the poor, like road safety and sexual violence. We’ll also consider things like tertiary education financing, where the opportunity for a successful family member to help an entire family move out of poverty. Because environmental degradation disproportionately affects the poor - and can even reverse progress made on other basic needs - we have an increasing focus on relevant environmental, conservation, and even climate solutions. Again, as we work with specific organizations, our most useful tool to understand our alignment with them is the 8-word mission statement.

A scalable solution.

A solution isn’t a solution without impact. Moreover, in our view, the “effect size” of that impact must be big enough to be consequential. Sometimes we have rigorous evidence of impact already, but since we mostly start with early-stage organizations, we’re usually focused on the potential for impact. That’s a judgement call. We make that call on the basis of:

Behavior.

Impact comes from behavior change, from people doing something different. We work with the organization to map out the key actors in terms of exactly who must do what differently all the way to impact. That accomplished, we look at the “drivers” - what the organization does to make each of those behaviors happen. Each behavior and its driver comprises a hypothesis. We need to buy that hypothesis; they need to prove it as soon as possible.

Logic.

If we have a behavior map and the corresponding drivers, we can systematically examine the logic of the whole chain of behaviors and drivers to judge whether the whole thing makes sense in the light of our experience with many solutions and organizations over time.

Links.

We look at where there are already rigorous established links in the literature between proposed drivers and behaviors, and between those behaviors and impact.

Behavior, logic, and links can often make a powerful case for potential impact. As the organization pushes the solution through the journey to scale, it is possible - and we expect - to measure behavior and then impact in successively more rigorous ways (see below in the due diligence section).

Once there seems to be real potential for impact, we look at scalability. A scalable solution is one that has the potential to make a big dent in a big social problem, maybe even solve the whole thing. The first step is to create a systematic model that can be systematically replicated. That model defines the solution. Four deceptively simple criteria determine whether that solution is scalable. We think of consequential impact as the first one: “Good enough.” The other three are:

- Big enough.

- Simple enough.

- Cheap enough.

To make a judgement based on those criteria you need to know the “doer” and “payer” at scale: You need to know who is going to replicate the solution—“do it”—at big scale and who is going to pay for it. You can’t answer any of the “enough” questions without knowing who will someday do the heavy lifting at problem-solving scale.

First, there are really only four potential doers at scale:

- The innovator. The originating organization becomes big enough to achieve scale

- Businesses. Lots of firms replicate a for-profit solution.

- NGOs. Lots of organizations deliver a nonprofit solution.

- Governments. Ministries and agencies deliver the solution as part of their services.

In the vast majority of cases, going to scale means that a solution has to escape the confines of the originating organization; “the innovator” is rarely a viable answer. There might be multiple doers midway through the journey to scale, but there is almost always one that ultimately predominates as you get into really big numbers. For example, a community health worker model might initially be replicated by other NGOs, but its potential can only be realized if governments adopt and implement it as policy. A single business might grow to an impressive size, but to solve the problem still requires that a bunch more businesses deliver some version of your solution. Increasingly, our experience points to governments and markets as the doers for most solutions at really big scale.

As for payers, there are again only four:

- Customers: when you’ve got a for-profit solution

- Private Philanthropy: when your solution requires some finite subsidy

- Government: budget allocation of tax revenues or Big Aid

- Big Aid: multilateral and bilateral funding directly to NGOs

As with doers, there may be a sequence of overlapping payers. Perhaps philanthropy gets things started, then there’s a transition to Big Aid down the line. Perhaps Big Aid pays at medium scale, but it’s government funding that comes in at much bigger scale. But it’s almost always the case that one payer will eventually do the heavy lifting.

You cannot judge scalability without identification of the doer and payer at scale. Once you have a sense of the most promising candidates, you can make a judgement of whether that solution is:

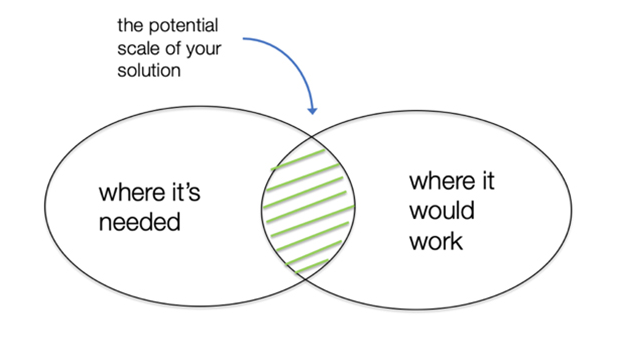

Big Enough

This is about the potential scope of the solution. Big enough means big enough to matter given the scale of the problem (or, perhaps, the scale of your ambitions). Here’s a useful Venn diagram:

The overlap between the two circles represents the “addressable market” for the solution. To figure it out, you first have to understand the nature and magnitude of the problem and where the need is most acute. Next you have to figure where the solution would work. You may already know the answer, or the organization may be in the middle of learning it the hard way. A useful tool for us is a systematic “where-it-would-work” list that explores the geophysical, political, cultural, economic, and other model-specific conditions necessary for the model to achieve real impact. For most organizations, this list becomes more honed and useful over time, often from hard lessons learned.

Big enough also means that, in aggregate, there are enough payers with: 1) sufficiently deep pockets to drive scale, and 2) willing to fund your solution. Big Aid actors won’t pay if they’re not interested in the problem; taxes won’t drive scale when the government in question doesn’t collect them; and, well, there’s rarely enough private philanthropy available to drive anything to scale (that’s not what it’s for). Big enough also means that there are enough competent potential doers operating in the areas of greatest need. No matter how good the solution, it goes nowhere if there isn’t anyone capable of replicating it well.

Simple Enough

Expressed as a question, this asks: “Is the solution simple enough for the doer to do it?” These are some general principles we find useful:

- The innovator replicating with a single organization—might be able to do something complicated at biggish scale, but you’ll have to build a large organization and endlessly raise - or earn - a ton of money. (With the possible exception of a few tech solutions, “the sole innovator” is pretty much never the answer.)

- Businesses can do pretty complicated stuff if it’s profitable enough, but simpler is still better.

- NGOs don’t have a very good track record of replicating others’ solutions while maintaining high quality. To repeat: the simpler, the better.

- Governments need things simple. Really simple.

If we’re unsure about whether the model is simple enough, we try to find some example in the context of the doer at scale —whether it’s a big international NGO, government ministry, small-to-medium enterprise, or something else—of that kind of organization having done a good job of delivering something as complex as your solution. If we can’t identify clear examples, the presumption is that the solution is too complicated, or too out of the realm of that particular doer. For example, governments rarely take on models that include somebody selling something. Businesses don’t take on activities that are a drag on the bottom line. actors .

Cheap Enough

Again, the relevant question asks:” Is the solution cheap enough that your payer would pay? Everybody has a price point, whether it’s a poor mother considering buying a clean cookstove for her family or a government minister looking at the cost of a new community health worker model. Determining that price point must be an early priority. Of course, the best way is to look at what people are already spending. If the lesson from a zillion efforts to sell clean cookstoves is that very poor people can’t or won’t pay more than about 10 bucks (it is), it’s going to need some very creative thinking to get a $50 stove into their homes. If a government currently spends $30 per person for health at the district level, and the proposed solution costs $60, there’s a problem.

The case of for-profits has an additional wrinkle. The product must be cheap enough for the customer, but provide enough margin for the business - the doer at scale for a high-impact business is other businesses, and no one will be motivated to imitate a business that is not sufficiently profitable. The difficulty here is that impact at significant scale then depends on an unbreakable alignment of profit and impact. This requirement narrows the pipeline of interesting for-profits.

The organization

Clarity around scale, impact, and scalability brings us to an examination of the characteristics of an organization able to deliver a solution toward its full potential. These are familiar to any investor in early-stage organizations and they focus on the leader and the leadership team. We must see persuasive evidence that the leader (supported by the team) is committed to impact at scale and can:

- Set strategy and change course as needed

- Oversee ongoing evolution of the model

- Raise money

- Attract talent

- Build and manage the organization

- Create a high-performance culture that, in this case, includes a demonstrable curiosity and rigor around impact.

Based on the stage of the organization, we look to make sure the right people are in the right key roles, and that the appropriate systems for performance management, information, and M&E are in place. Finally we look for momentum, that gestalt sense of accelerating progress over time.

Should We Stay (In) Or Should We Go

A Portfolio Management Framework For Impact At Scale

Once we have identified promising solutions and the organizations that can deliver them, we manage with a framework based on the notion that the journey to scale involves a common pathway through a set of observable stages. This framework can be used to both manage the portfolio and advise the specific organizations within it.

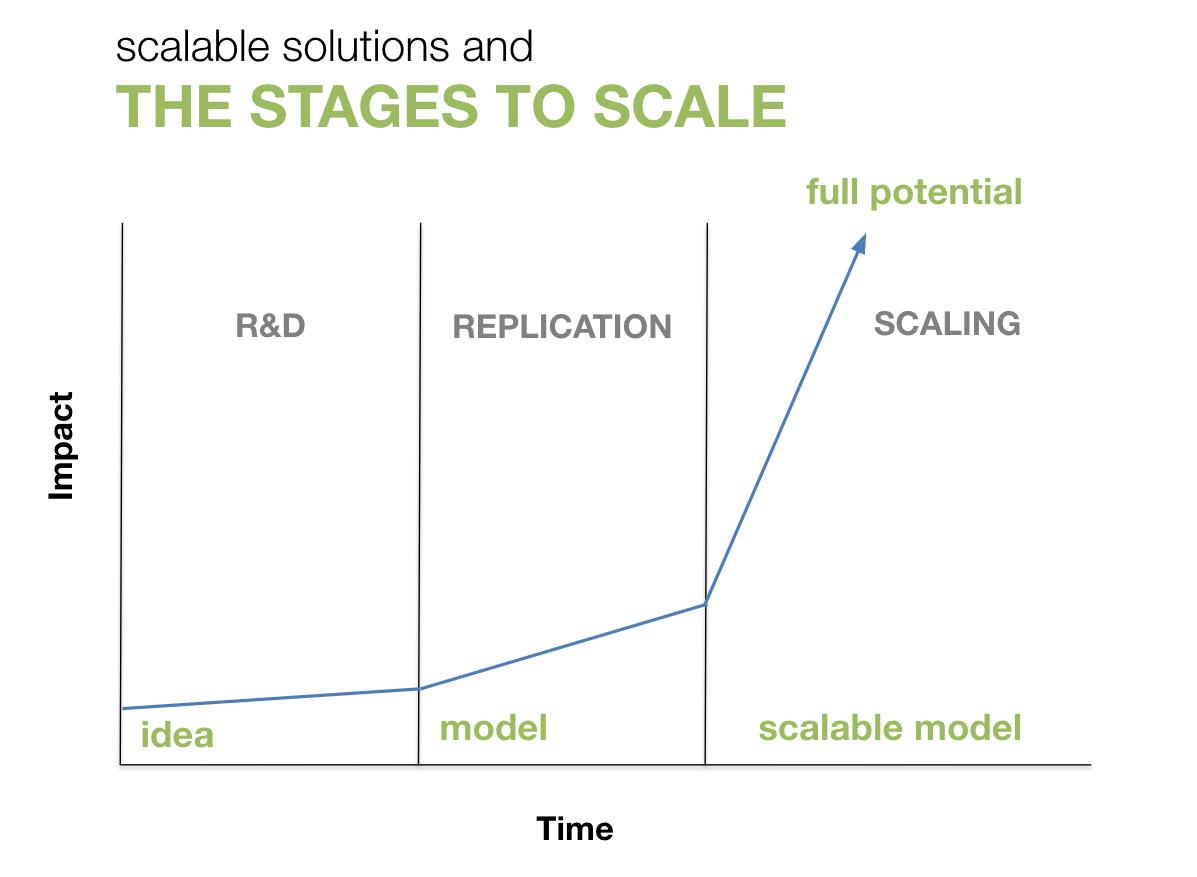

There are three distinct stages on the journey to scale: R&D, Replication, and Scaling. The R&D stage begins with the idea, and goes through the design and iteration needed to get to an initial replicable model that shows persuasive promise of scalability and impact. Replication is about growth of replication, with continual iteration toward scalability and efficiency of operations, along with the achievement of rigorous evidence of impact. Scaling stage is characterized by a chromatin increase in the rate of replication, an increase that typically involves the increasing recruitment and facilitation of organizations that constitute the doer-at-scale. There is no neat boundary between the stages; but while they do tend to bleed into each other, the criteria for completion of each stage is clear.

Within this framework, a detailed understanding of 1) the observable criteria for graduation into the next stage and a grasp of the core functions of the organization while in a particular stage allow us to locate where that organization is at present and how it is progressing on the journey to scale over time. Here is how we look at each of those stages:

R&D

In R&D, the organization functions mainly as a lab, moving from an initial idea through the design and iteration of a systematic, replicable model. Its chief role is one of continual experimentation informed by ongoing investigation into the relevant literature and the experience of other organizations. R&D should be characterized by a slow rate of growth, if any: what’s important is that it is of the right size and in the right place(s) for optimal development of a high-potential model.

The organization graduates from R&D into impact when it has:

- Developed and articulated a systematic, replicable model for delivery of the solution.

- Made a persuasive initial case that the solution is big enough, simple enough, and cheap enough.

- Made a persuasive initial case for impact.

We say “a persuasive case for impact” because it is necessary to have reason to believe there is impact worth carrying forward, but the sample size is too small and the rate of ongoing iteration too great to justify an expensive study that requires a lengthy interval between start and finish. A “persuasive case” is constructed as a package that typically includes:

- A clear and logical Mulago theory of change, as described above.

- Existing evidence that supports as many elements as possible of the theory of change

- Growing evidence from the organization’s own experiments and monitoring.

Replication

If R&D is a lab, replication is a factory. This is when the replication of the model begins and when the organization and operations grow. While all good organizations continue to do important R&D in all stages, the organization’s focusin replication stage is on operations, the mechanics of replication, and preparations for going to scale. It’s useful to think about the replication stage having an early and late phase.

In Early Replication, the organization refines critical elements of the model and the mechanics of replication by doing a lot more of it. It’s about honing the model and working to squeeze more impact out of it. It’s about continued iteration toward maximum scalability in terms of Big, Simple, and Cheap enough. The critical tasks are:

- Refining the “where it would work list,” to better understand where maximum impact is to be had. This may lead to an initial shrinkage of potential reach as hard lessons are learned.

- Structuring the team for growth.

- Defining the unit of replication and determining unit costs.

- Lowering unit costs as a more sophisticated understanding of “cheap enough” emerges.

- Simplifying the model as it becomes clear what’s essential and what’s not.

- Hiring in the right operations people.

- Putting in the right information, performance management, and M&E systems.

Late Replication is concerned with all these things, but there is an increasing focus on those things that will collectively serve to drive scale, the elements of what we call the Big Shift. Because a focus on at least most of them are essential for scale, these elements can be usefully represented as a checklist:

- Doer @ Scale - The organization begins to shift the heavy lifting of replication onto other organizations.

- Payer @ Scale - the funding of replication shifts from early-stage - typically philanthropic - funding to next-level funders and on to the ultimate payer @ Scale.

- Model - the model must be continually iterated toward better, bigger, simpler, cheaper.

- Tech - the organization finds ways to use digital and other merging technologies to extend its reach, lower transaction costs, and achieve other efficiencies.

- Policy - the organization uses its increased visibility and deeper understanding of barriers and opportunities to push change key policy changes.

- Collective action - the organization becomes part of a movement, network, or coalition to advance adoption of the solution.

While not all of these are necessarily essential to every organization, late replication is about exploring how each might be exploited, especially the near-universal priority of replication by other doers.

The other thing that must be achieved before there is an attempt to scale the solution is rigorous evidence of impact. This is the time when it is necessary to do the big RCT of other well-conceived study by a third party to determine the impact of the model. Nothing should scale without rigorous evidence of impact.

The organization graduates from replication into scale when it has:

- lowered costs, simplified the model, and better targeted “where it would work.”

- demonstrably engaged the elements of the Big Shift

- made a rigorous case for impact.

- demonstrated an initial, steep uptick in growth.

Scale

Scale stage is when the replication curve - now rigorously correlated with impact - steepens in a sustained way. The initial escape from linear growth can come as a result of progress on any of the elements of the Big Shift, but sustained non-linear growth is usually because of increasing success at transferring the burden of replication onto the doer at scale.

There are often four observable phases of scale. The first is when the organization itself figures out something - fundraising, tech, policy, ops, etc - that triggers a growth spurt. The second is when the organization begins to engage other doers, but successful replication requires an intensive and expensive engagement on the part of the organization. The third is when that engagement becomes much lighter because the organization has figured out better recruitment and teaching methods. And finally, real scale is in sight when replication by the doer at scale escapes the orbit of the originating organization entirely and the solution simply becomes the way things are done.

If there is not movement from one phase to the next, impact often will plateau, turning the hockey stick into an S-curve, and growth of impact sputters to a halt. Unless someone figures out a way to accelerate replication again, it’s time for us to exit.

While the originating organization may continue its own linear replication overall, its primary role must shift into one of recruitment, facilitation and quality assurance.

This graphic illustrates this Journey To Scale framework:

We get in when there is the promise of impact at scale, we stay in when we continue to believe it, and we exit when we don’t believe it’s going to happen. This is how the framework plays into our overall approach to portfolio management.

Fellows program

Mulago has two fellows programs - the Rainer Arnhold Fellows, focused on solutions to poverty, and the Henry Arnhold Fellows, focused on environmental solutions. These programs serve as the onramp for almost all of the organizations in the Mulago portfolio. The fellows are founders whose ideas and capabilities whom we judge, in a structured but light process, to have high potential for impact at scale.

The fellowship is a two-year program. The centerpiece is a week-long intensive course in each of the two years that is focused on design for impact, strategy for scale, and key aspects of building the organization. We also visit them on site, and we speak with them frequently in office hours. By the end of the program, we know them, their solution, and their organization well.

At the second year of the fellowship, each of the fellows formulates a set of milestones for the year ahead. At the end of the fellowship, we make a decision as to whether to add the fellow’s organization to the portfolio per the explicit criteria based on mission, scalability, and ability to deliver. Over the last five years, about 70% of the fellows enter into the portfolio. While we focus intensively on teaching and supporting the fellows, it is very much the case that our two years with a fellow represents a particularly deep form of due diligence.

The Milestones process

Our ongoing portfolio management centers around a formal and systematic process of annual milestones that are formulated in collaboration with the organization. It is a way of getting to a shared sense of priorities and goals: the organization does the first draft.

The first and most important ingredient of the milestones process is the Big Picture. Here, we lay out the core elements that make sure we’re both on the same page, well-aligned, and on the same journey. The Big Picture is expressed in the skins of simple terms you can only get to by understanding the solution in all of its complexity. It includes:

- The Solution

- The Idea (In ~6 words)

- The Mission (in 8 words or less)

- The Theory (In a single sentence that takes the form of “If we take action X, they will do action Y, and the result will be outcome Z.”)

- The Model (Summarized as ~4 headline elements).

- The Strategy (In 2 lines, one naming the doer-at- scale, the other payer-at-scale.)

- An estimate of the potential of the solution based on an analysis where it’s needed and where it would work.

- A definition of success, including the impact metric(s) that best captures fulfillment of the mission

- The doer/payer/big shift-based scale strategy: one line each on the current thinking about how to:

- Achieve replication the proposed doer-at-scale

- Achieve funding via the proposed payer-at-scale

- Make best use of tech to extend reach and lower transaction costs.

- Tweak the model for more impact.

- Address enabling policy

- Spur collective action.

- Three-year ambition in terms of size of 1) direct implementation goals and 2) explicit movement along the stages of the journey to scale.

The Big Picture, when made as simple as possible, is the centerpiece of our due diligence and management. Until it’s done, neither party knows if we’re working on the same thing, and the goal is to make it ever sharper and clearer: this is a critically important opportunity to get to a necessary shared reality. It is a snapshot in time, though, and expect there will be some iterative changes year to year.\Once the Big Picture is laid out, the milestones document lays out a short list of priority goals in each of three categories: delivery, organization, and impact:

Once the Big Picture is laid out, the milestones document lays out a short list of priority goals in each of three categories: delivery, organization, and impact:

- Delivery includes the implementation goals - how many beneficiaries are to be engaged, what geographical area is to be covered, etc - along with iterations to the solution (making it cheaper, simpler, more broadly relevant)and implementation of the scale strategy (engaging the doer/payer or big initiatives in technology, policy or collective action)

- Organization covers the money to be raised, hires to make, new teams to build, systems to be put in place, and changes to the organization’s governance

- Impact includes new M&E systems, key research in motion, and the impact they hope to achieve.

Drafts are batted back and forth in an intensive set of conversations until a version is arrived at that both parties feel is ambitious and realistic. In those conversations we also learn a great deal about the quality of leadership and the culture of the organization. At the end of the year, the organization submits a report on progress that includes a brief comment on each of the milestones. This is not a blunt-instrument report card, but a way of understanding what happened in the past year in the real world of new obstacles and opportunities.

We also do a lot of site visits. Our goal with a visit is to understand the local context, get a thorough sense of the model and how it works, and get to know the team. We rarely make an initial funding decision without a site visit, and subsequently we prioritize visits to see active Fellows. We generally see portfolio organizations every 2-3 years.

We get quarterly “headlines” from organizations - letting us know if there have been any major changes to the milestones along with key organizational achievements and challenges. In the spirit of minimal hassle, we accept everything from a short email to a quarterly report they are already doing for their board or other significant funders. We speak to them frequently in office hours and other spontaneous conversations.

Impact

Impact - its achievement and ongoing measurement - is of course an ongoing preoccupation. Our expectation is that an organization builds a compelling body of evidence over time. In the R&D phase we’re looking for data - both qualitative and quantitative - that indicates they’re on to something quite promising. This could be as simple as a good monitoring system. In the build towards scale we expect the rigor of the evidence and the monitoring systems to become much more sophisticated.

Regardless of the stage, we work with each organization in our portfolio to formulate a methodology to demonstrate and quantify their impact. Each organization must lay out

- What they are trying to accomplish - i.e. the outcome from the 8-word mission statement.

- The metrics that best capture that outcome

- How they get high-quality numbers that show a change

- A persuasive case for attribution: “what happened with you minus what would have happened without you.”

Our approach to impact measurement is that it should be “simple enough to do and rigorous to mean something.” We think that well-designed and implemented ongoing measurement of impact by the organization is better than occasional, more rigorous snapshots. We think that accuracy is more important than precision. We know that at key points in the journey to scale it is absolutely essential to have rigorous evaluations - RCTs or an appropriate equivalent - by qualified third parties. As we noted above, we expect the organization to continually develop an increasingly robust body of evidence over time.

It should be noted that it's not one thing that gives us confidence - not A/B tests, not customer interviews, not one before/after study, not a single RCT. It's a collection of data - different kinds of data gathered in different ways - and all grounded in a clear mission and outcome - that gives us a comfortable degree of confidence.

Cost

While nothing should scale without real impact, nothing can scale if it costs too much. As discussed earlier, what is “cheap enough” depends on the price point, the amount that the payer-at-scale is willing to pay. When an organization and an idea are early in their evolution, it is impossible to estimate costs of delivery and impact with much certainty. Like impact itself, the understanding of costs is the result of a process that drives the emergence of increasingly credible numbers over time. Here’s what we look for a the different stages:

- Idea: a credible “guesstimate” based on the costs of comparable efforts

- R&D: a credible projection based on an emerging understanding of real costs

- Replication: an increasingly accurate estimate based on more accurate - and lowered - unit costs and a better understanding of impact.

- Scale: definitive determination of the cost per unit impact in terms of the mission.

We do not try to compare the value of things across sectors. Unlike those in the “effective altruist” movement, we don’t believe that you can compare the value of a livelihood with a child’s life saved with a secondary education. Everything we invest has passed the screen of “a basic need of the poor” and beyond that, value is in the eyes of the payer.

Funding decisions

All of this information is integrated through the lens of the larger “journey to scale” framework. The subsequent funding decisions are made through a process of team judgement and consensus on progress to date, current momentum, and the prospects for impact at scale. Funding decisions, like any investment decision, require a big dollop of judgement, but a systematic framework informs and makes that judgement more valuable. Our judgement has been honed by two decades of watching real progress - or not - of committed organizations. The emergence of a team of talented generalists armed with a systematic framework has brought a richness of varied experiences and diverse viewpoints that makes for an effective consensus process.

When we get out.

We have the great good fortune of being able to provide long-term funding for organizations that are successfully moving solutions toward their full potential. We stay in when we believe the promise of impact at scale; we get out when we don’t buy it anymore. There can be any number of reasons for that loss of confidence: an RCT demonstrating that the solution just doesn’t work, chronic leadership/management issues, the inability to raise money (sometimes simply because of big - often unjustified - shifts in the funding environment), failure to establish a workable doer-at-scale, and fatal run of bad luck - the list is long. It is often the case that it is not the organization’s “fault:” Despite the best of efforts, sometimes things just don’t work out.

We never rush for the exit. Yes, these long term relationships generate a great deal of empathy for these inspiring doers - along with sympathy when things go south - but we work not to let that delay decisions. It has more to do with realism: they work in settings of market and government failure, and general unpredictability. There is a huge potential opportunity cost for getting scared and getting out too early; we have seen too many capable and committed organizations come back from devastating setbacks. We get out when we simply can’t see a way to get back on the track to scale. Exits are the hardest part of our work by far, but when necessary, they’re central to fulfilling the obligation of an accountable funder.

Making ourselves accountable.

Our consensus process also allows us to “place the dot” - to mark what we believe to be the current position of the organization and solution on the journey to scale. The criteria for moving from one stage to the next allows us to place that dot with a satisfying degree of objectivity and precision. We do so in collaboration with the organization in question, and it is the sequential “placing of the dot” that allows us to document progress - or not - toward the ultimate goal of fulfilling the potential of the solution.

And it is the movement of the dots across our portfolio that defines our success as an investor in “lasting change at scale,” and what makes possible a transparent accountability for it. As evidence of a solution’s impact accumulates, the movement of the dot comes to be a continually more powerful indicator of momentum, achievement, and the promise of impact at scale. Placing the dot may seem like an overly simple way to mark something so important, but there is so much systematic effort and rigorous analysis behind that we are comfortable this is an appropriately sophisticated marker.

In the end, this approach forces us to live up to our investment thesis and whatever claims we make for our approach. It will never be perfect; it will always be aspirational. But as funders, we have the easy part of lasting change at scale. We want to keep our feet to the fire; we hope this helps and inspires others to do the same.

Download a PDF of Making Ourselves Accountable

Impact in your inbox

The best stuff we run into, straight to your inbox. Zero spam, promise. To see past issues, click here.